Emona, Legacy of a Roman City

Emergence of Emona

The Roman occupation of the wider Ljubljana area is linked to the conquest of the Balkans by Augustus. Archaeological investigation in Ljubljana in 2008 yielded the traces of two military camps in the area where the navigable Ljubljanica River came closest to the castle hill, below which ran the main road link towards the Balkans. Behind the first camp two defensive ditches were excavated, and west of the ditches a defensive embankment. The soldiers lived in tents. At the beginning of the 1st century CE, on the left bank the walls of this camp were levelled with the ground and the ditches filled in, and then a large part of this area was developed with wooden huts to house the soldiers who built Emona.

In the first decade of the 1st century CE, in the area of what is now Ljubljana, along the left bank of the Ljubljanica River, the Romans established their colony of Julia Emona. From the inscription stone discovered nearly a century ago, we know that Emona already stood in the second half of the year 14 CE or the beginning of the year 15 CE, and that within it the emperors Augustus and Tiberius ordered the construction of a large public building perhaps, as envisaged by the reconstruction in the writing of Jaroslav Šašel, a walled fortification with towers. The city was settled by colonists from northern Italy. We know the names of around 30 families that settled in Emona; of these 13 were from northern Italy, mainly from the Po River valley.

As a result of archaeological research conducted in the centre of Ljubljana, in recent years we have found out a great deal about the pre-Roman, ancient settlement of Ljubljana. The beginnings of Ljubljana can be traced back to the proto-urban settlement under the Castle Hill, in the area of the modern-day district of Prule, which emerged in the 10th century BCE. The builders carefully planned their settlement. A proper grid of streets was adapted to the terrain and the streets were laid with gravel. Along them were lined wooden buildings, each with one or more rooms. The buildings were renovated and reconstructed several times, yet nevertheless the basic plan of the settlement did not change significantly. The cemetery for the inhabitants of this settlement lay on the other side of the Ljubljanica River.

The settlement below the castle hill enjoyed renewed vigour from the 3rd century BCE on. In the 1st century BCE the ancient inhabitants traded intensively with the Romans, and the Ljubljanica River played an important part as a transport route. Later, when the colony of Emona was already established, the settled area below the castle hill existed as a suburb of Emona.

Roman city of Emona

The Roman Empire was an extraordinary achievement. At its height, in the 2nd century CE, it comprised 60 million inhabitants living in an area covering 5 million km²: from Hadrian’s Wall in northern England to the Euphrates in Syria, from the Rhine-Danube river routes that linked Central Europe with the Black Sea to the North African coast and Egypt. During the Emona period, the area of modern-day Slovenia was incorporated into the Roman Empire and it acquired some of the key gains of Roman culture: urbanisation, literacy and the Roman residential culture.

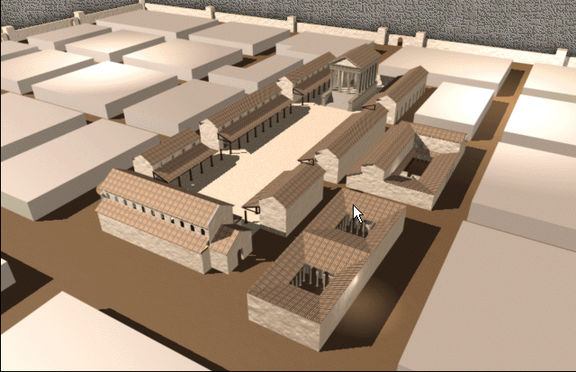

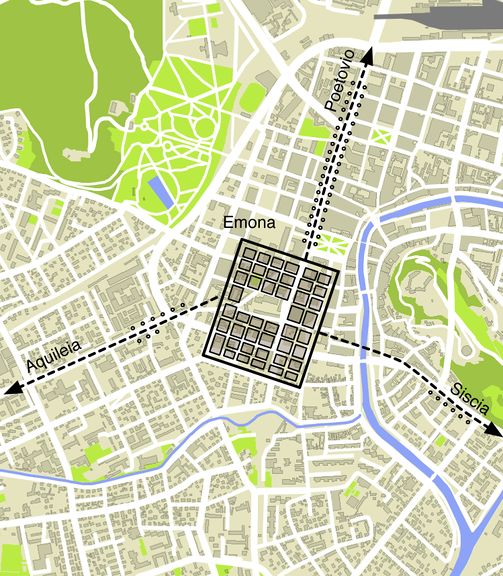

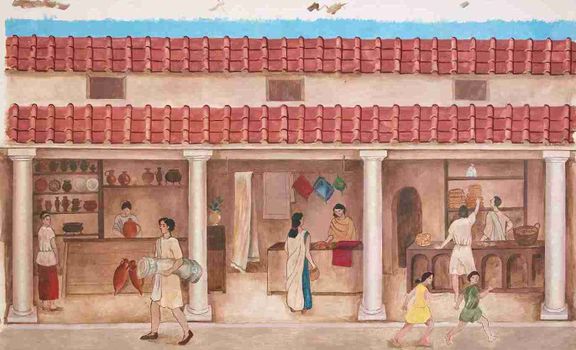

Emona flourished from the 1st to the 5th century. It was laid out in a rectangle with a central square or forum and a system of rectangular intersecting streets, between which were sites for buildings. Under the streets, running west-east flowed the cloaca, a major drainage channel that carried waste water into the Ljubljanica. The city was enclosed by walls and towers, and in places also by one or two ditches filled with water. Some areas beyond the walls were also settled; the potters’ quarter behind the northern wall is well known. Along the northern, western and eastern thoroughfares into the city – from the directions of Celeia, Aquileia and Neviodunum – cemeteries became established, according to Roman custom. In the 1960s, the northern cemetery in particular was thoroughly researched.

As a Roman colony, Emona had extensive pertaining territory for which it was the administrative, political, economic and cultural centre. Emona’s administrative territory or ager stretched from Atrans (Trojane) along the Karavanke mountains towards the north. In the east, the boundary ran somewhere near Višnja Gora, and in the south probably along the Kolpa River. In the west, the territory of Emona bordered that of Aquileia at the village of Bevke in the Ljubljansko barje wetland.

Surveyors measured part of the Emona ager and divided it into agricultural holdings. As in the majority of Roman cities, the main activity of Emona’s inhabitants was agriculture, working the fertile land they had been granted around the city. In Roman times, a land holding meant more than just land for cultivation; ownership of land meant individual wealth and social standing.

The wider area of Emona saw the development of typical Roman rural infrastructure: villages, hamlets, estates and brickworks. The small towns became local centres and markets: Karnij in the area of modern-day Kranj, Navport in the area of Vrhnika, and in the area of modern-day Ig and Mengeš, settlements whose Roman names have been lost.

Alongside its road links, the waterway of the Ljubljanica was very important for Emona. From prehistoric times right up to the construction of the railway in the 19th century, it was an important trade route that linked the northern Adriatic and the Danube region. The mass of finds from the bottom of the Ljubljanica that can be dated to the middle Stone Age and later, indicate that the Ljubljanica was also an important cult area. The Ljubljanica probably had associations with the pre-Roman deities of Laburus and Aequorna. Aequorna was a very popular deity in Emona – perhaps she was the deity of the nearby Barje wetland, and Laburus the local water god.

From its creation to its collapse, Emona was closely tied to events in the Roman Empire. Its geographical position meant it played an important part in the Empire’s military defence system. From the second half of the 4th century right up to the Hungarian incursions in the 10th century, this area was an important transit territory on the route to the Apennine peninsula. Research of Emona has confirmed its important role in the period of late Antiquity , when it was the first major station in support of the newly established defensive line across the Alps, Claustra Alpium Iuliarum. Linked to this are some extensive new constructions at Emona in the 4th century, chiefly the public bath house in the area of the planned new university library, where numerous finds with a military association indicate the major concentration of reinforcement troops in Emona or nearby.

From the late 4th to the late 6th century, Emona was the seat of a bishopric. The intensive contacts pursued by the early Christian community of Emona with the ecclesiastical circle of Milan are reflected in the architecture of the early Christian complex along Erjavčeva Street and in two preserved letters from St. Hieronymus to the nuns of Emona and the monk Anthony.

In the late Roman period, the image of Emona gradually changed: some entrance ways through the walls were filled in, while the cleaning and maintenance of the cloaca and city ditches were neglected. In the 5th and 6th centuries, effectively the only new constructions of any architectural quality were ecclesiastical buildings. In view of similar cases elsewhere in the Roman Empire, for instance in Gaul, we can say that this did not indicate the collapse of the city, but a change in the urban identity of Emona, which reflected changes in the thinking of the Emonans, in the priorities and role of the city at that time. Secular architecture and infrastructure was clearly no longer important, with major concern and financial input focused on architecture linked to the early Christian Church, whose power at that time was growing rapidly. In cities throughout the Empire, bishops at this time were no longer just Church dignitaries, but were taking on administrative functions. In short, the change in the image of Emona in late Antiquity reflects the change in the internal world of the Emonans, the change in their identity, and the administrative changes with the disintegration of the Empire.

In the period from the 4th to the 6th century, the Roman Empire gradually fell apart. The governing authority became increasingly decentralised, communication between individual parts of the Empire deteriorated and the Roman system of administration lost its grip. During this period, the Empire encountered numerous tribes referred to by the Romans with the generic name “barbarian”. These people sought better living conditions in the Empire: money, fertile land, slaves and steady work. Some of these people stopped in the area of Emona. The Visigoths camped by Emona in the winter of 408/9, the Huns inflicted themselves on it during their campaign of 452, the Langobards passed through on their way to Italy in 568, and then came incursions by the Avars and Slavs. After the first half of the 6th century, there was no life left in Emona.

We know the archaeologically researched cemetery in the northern part of Ljubljana, in Dravlje, to be from the period at the end of the 5th and beginning of the 6th centuries, when the wider Ljubljana area was ruled by the Ostrogoths from Italy. Members of the Ostrogoth military station and ancient inhabitants are buried there in more than 50 graves laid out in rows. Despite the reports in Roman sources of arson, slaughter and devastation as the barbarians invaded , the cemetery in Dravlje, along with other archaeological sources, indicate that the invaders and original inhabitants were able to live side by side for several decades.

Heritage of Emona and identity of Ljubljana

When did the people of Ljubljana start thinking about the Roman precursor to Ljubljana? Where and how did they search for Emona?

Finds from Roman Emona came to light in just about every construction project in the centre of Ljubljana. Archaeological excavations under expert leadership only began at the end of the 19th century, when Alfons Müller investigated part of the northern Emona cemetery in 1898. Intensive archaeological research of Emona therefore dates back only over the past 100 years, although the people of Ljubljana had searched for Emona, told stories about it, portrayed it and set its monuments up in public places at least from the 17th century on. In that first period the investigation of Emona was tied to the story of the Argonauts.

After a hiatus, when Ljubljana and its people joined in the search for their identity in the national dimension, major archaeological excavations of Emona started at the beginning of the 20th century, when the southern part of the Roman city was unearthed. This prompted the then Ljubljana city council to protect the entire complex south of Rimska ("Roman") Street for the excavation, research and presentation of Emona and for a planned Emona Museum. However, when Ljubljana started expanding rapidly after the First World War, the Ljubljana administrative forum divided up the area between Gradaščica and today’s Aškerčeva Street into lots, and started selling off these lots to private individuals to build on. The Roman wall stood right in the middle of the land that would supposedly support a major round of construction, so a proposal was made to simply pull it down. The arguments against the wall were based on its poor condition and its position, since it supposedly impeded traffic in that part of Ljubljana.

The then head of the monuments office, France Stelé, was resolutely in favour of the band including the Roman wall being excepted from the land offered for sale. His efforts and the efforts of like-minded people influenced public opinion, and the city council bowed to pressure, backing off from the planned demolition. In 1926, on the proposal of the Conservation Society the City of Ljubljana decided to restore the wall according to plans designed by Jože Plečnik. After numerous heated debates, work on restoring the wall only began in 1934; the main works were completed by 1936. Jože Plečnik fundamentally redesigned the remains of the Roman walls: he had two new passages drilled through them, to create a link to Snežniška and Murnikova Streets, and behind the walls he arranged a park displaying architectural elements from Antiquity, constructing a lapidarium in the Emona city gate. On the road side of the wall he had an avenue of poplars planted. By the former main entrance to Emona he erected six columns, closed the gate up with an old metal door and arranged the lapidarium. Above the passageway to Murnikova Street he set up a pyramid, which he covered with turf.

At this time Emona signified for the people of Ljubljana, as it did during the Baroque, a distinguished, civilised forebear. In contrast to the second half of the 20th century, when the heritage of Emona was protected in documentary form at all costs, and when monuments were supposed to be primarily testaments, the first half of the 20th century featured a different approach to Emona’s heritage: the remains of Emona were transformed, taken as an inspiration for reworking, for adding new elements, for a collage of old and new – as illustrated by the story of Plečnik's transformation of the Mirje area.

The next period of intensive interest among the people of Ljubljana in the heritage of Emona came after the Second World War, especially in the 1960s and 1970s. Towards the end of the 20th century there was a key shift in the field of heritage management: heritage was no longer a subject of interest among the elite, but was now a subject of exceptional effort from a wider swath of public groups, who were fiercely determined to rescue and glorify everything inherited from the past. In describing the determination inherent in the efforts to save heritage, David Lowenthal and like-minded people use metaphors taken from religious contexts, describing it as a "crusade". Indeed they take the view that heritage in this period is a form of "secular religion", since it does not require rational facts and evidence, but faith.

In the case of Emona heritage, the second half of the 20th century was also a time of major reconstruction in Ljubljana, and this meant extensive archaeological excavations of Emona. A different kind of attitude towards heritage, oriented towards the urgent need to preserve monuments – in their most authentic form, with minimum encroachment on their historical testament – was at this time gradually built into the system of monument protection legislation. For this reason excavations generally kept pace with the equally extensive and ambitious presentation plans: Mušič’s presentation complex of Mirje, the grandiose plans to arrange the Jakopič Gardens in the complex with a museum in Frtica, the establishing of two archaeological parks (Emona House in the south-eastern corner of the former settlement; the Early Christian Centre archaeological park lies in the north-western part of the former Roman city, close to Cankarjev dom). Other, smaller presentation groups were ranged across the entire section of the former Roman city: the cloaca along Aškerčeva Street, the foundations of the basilica in the Jakopič Gallery, part of the western wall at Cankarjev dom, part of the northern wall by the exit from the Maximarket passage, in Josipina Turnograjska Street, and the northern gate of Emona, now the location of the Bukvarna shop and the statue of the Emonan, and so on. This period also saw a range of attempts to embed references to Emona into the urban image of Ljubljana: the Roman forum as part of what are called the Ferant apartment blocks, the trace of the Emona rotunda, and the paving indicating the grid of excavated city blocks in Trg republike square.

Archaeological research of Emona in the 1960s and 1970s produced frequent and persistent reaction in the newspapers. During this period the name Emona (and others associated with Antiquity, such as Mercator, Merkur and Viator) was used widely as a trademark in retail, business and education: the retail chain Emona, Emona karate club, Emona folklore group, the Emonska klet ("Emona Cellar") restaurant and so forth.

During this period of shaping Emona’s heritage, the period of Emona was presented as a time of the first civilisation, and the city itself as a progressive and largely modern urban construction. Various articles and papers referring to Emona consistently place at the forefront the municipal order of Emona and its "central" heating. Emona was presented as a dignified, cultured ancestor during that period of the modern, largely reconstructed, Ljubljana – an ancestor to which Ljubljana may refer with pride.

Emona today

The period from the 1960s to the end of the 1980s was a time of great popularity for Emona and its heritage. At the same time, the 1980s saw the start of a turnaround in how the past was viewed in Slovenia, a turnaround that changed the attitude towards the heritage of Emona over the next two decades. During the disintegration of Yugoslavia, the nations within it, including the Slovenes, sought and generated myths about their beginnings and about sui generis. The independence aspirations of Slovenia were lent gravitas by the search and "discovery" of an autochthonous origin of the Slovenes in the pre-Slavic Veneti, despite the extensive and repeated objections of experts. The Veneti myth became broadly popular, and the Slovenian state uses symbols associated with it on official documents and official gifts.

Nowadays there is less talk about Emona, and most importantly, the talk is different. There is no longer any talk of Emona as a distant and distinguished ancestor of Ljubljana, and the research of Emona raises questions about the purpose of environmental encroachments, the need for new construction, and the influence of capital. The heritage of Emona is in the background of these debates, either as a scapegoat for construction delays or as an argument against encroachments. More than ever before, there is an intense response from the lay public to the archaeological discoveries and questions about what will happen to this heritage. Some civil initiatives assess the Emona heritage as priceless, and use it as a tool for restricting environmental encroachments. For the first time we are also hearing clearly expressed and resolutely conveyed doubts about the ability of archaeologists to judge what heritage is worth protecting, and doubts about their capacity to protect such heritage adequately.

How should this be understood? The tensions between various interests and the conflicts between them are a permanent feature of urban areas. It is clear that heritage has varying and frequently opposing values for different groups, and opposing interests, which often lead to disagreement. Part of heritage management is managing and mitigating disputes surrounding archaeological sites and monuments. The city is undoubtedly a space where there will be constant conflict between capital, between investors, for whom heritage represents an obstacle and cost in developing expensive building land, and between the profession and various civil initiatives.

Moreover, in the late 20th century, during the "heritage crusade", how we view the role of heritage in society also changed. It is now the case that the past is the property of all, and that we create it and replicate it today, so no institution or profession can appropriate an exclusive interpretation of heritage, and in the opinion of certain archaeologists one of the important roles of archaeology is to enable various interest groups to participate actively in the process of interpreting heritage and deciding about it.

The growing interest among the general public in heritage is therefore being seen increasingly as a desire for active participation in the process of preserving and making use of it. Undoubtedly the previously privileged interest of archaeology will increasingly be just one of many interests of various groups and individuals in the process of preserving, interpreting and making use of the Emona heritage. Meanwhile, the active role of archaeologists in protecting and safeguarding heritage remains the ethical premise of that profession.

Written and adapted by Bernarda Županek, Curator for the Antique at Museum and Galleries of Ljubljana. The integral text was published in the catalogue Emona, Myth and Reality (Museum and Galleries of Ljubljana, 2010). Published on Culture.si with her kind permission.

External links

- Roman Emona web page

- Emona on Wikipedia

- Roman Castrum on Wikipedia

- About Emona on the Visit Ljubljana website

See also

- Roman Emona (in short)

- City Museum of Ljubljana

- Jakopič Gallery