The Hidden Gems of Slovenian Museums

East Asian collections from the turn to the 20th century

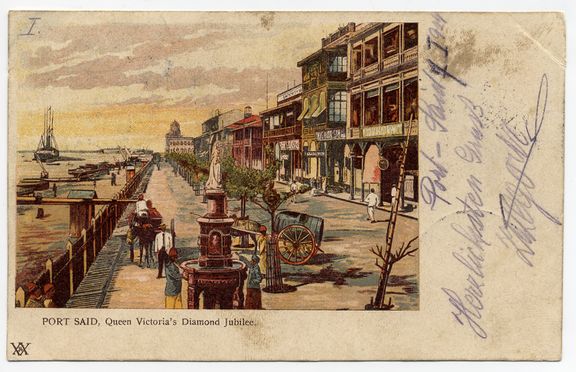

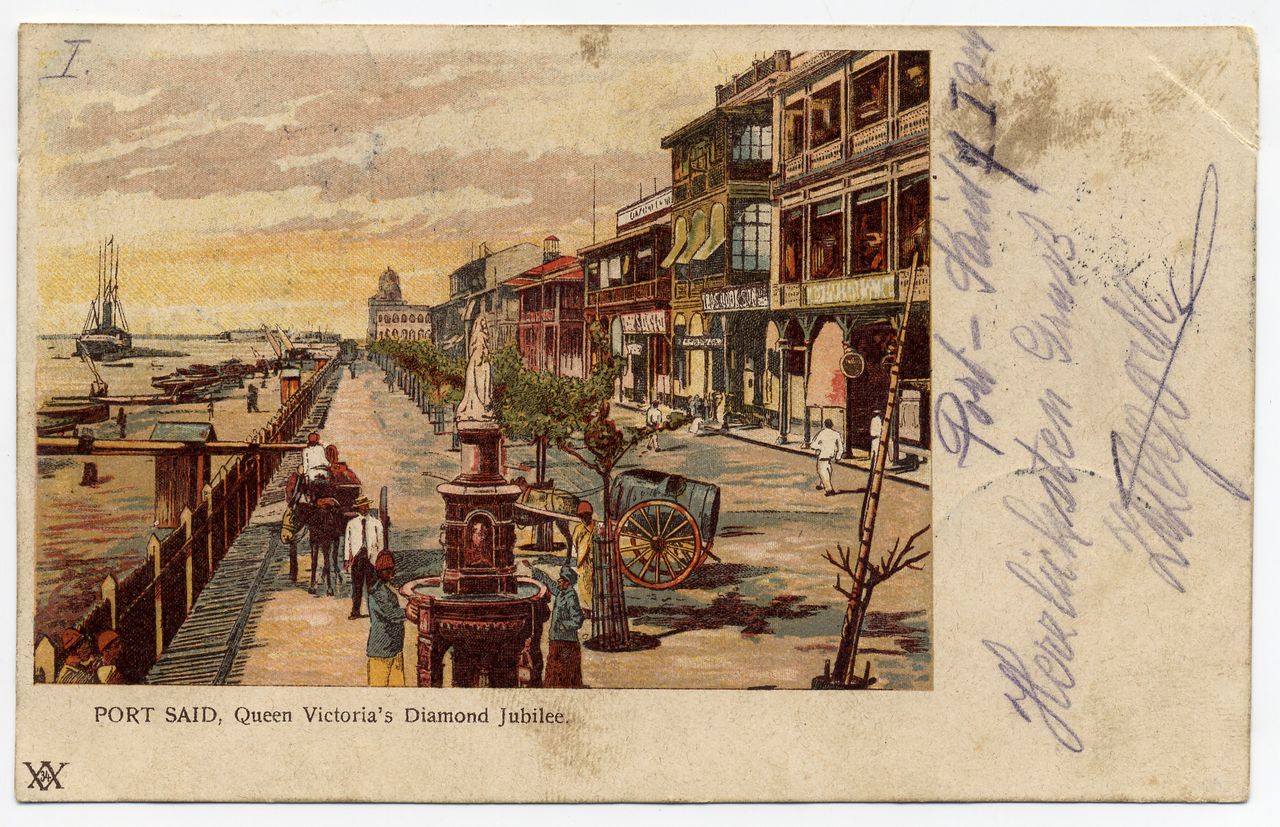

An antique postcard depicting Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in Port Said, Egypt, the stopping point for nearly every ship that sailed through the Suez Canal. Ivan Koršič Postcard Collection, Sergej Mašera Maritime Museum, Piran.

An antique postcard depicting Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in Port Said, Egypt, the stopping point for nearly every ship that sailed through the Suez Canal. Ivan Koršič Postcard Collection, Sergej Mašera Maritime Museum, Piran.

Constituting peripheral lands of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, what is today's Slovenia doesn't rank high in the history of travel and exchange between Asia and Europe. Before the last decades of the 19th century, sojourners from these parts were rare in East Asia. Most of them were missionaries, such as the Jesuit astronomer and mathematician Ferdinand Augustin Hallerstein (1703–1774) who worked as the Head of the Imperial Board of Astronomy in the Qing Dynasty court from 1746 until his death. Things started to change when the Suez Canal opened in 1869, and the Austrian-Hungarian navy gained a slight advantage over other imperial competitors in Europe.

Contacts between Slovenian lands and East Asia increased through travels to the Far East and trade networks. The latter were strengthened with the railway connection Vienna-Ljubljana-Trieste, completed a decade earlier. East Asian objects began to circulate on a greater scale, first as curiosities, then as souvenirs and decorative objects and eventually as collectables in their own right. After decades of gathering dust in museum depots, they have now been given a new lease of life in the digital library East Asian Collections in Slovenia, an ongoing project of the Department of Asian Studies at Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana.

The East Asian Collections in Slovenia website is the first to link the items from East Asia that can be found in Slovenian museums.

The East Asian Collections in Slovenia website is the first to link the items from East Asia that can be found in Slovenian museums.

Fashionable exotica

The earliest objects from East Asia can be found in the Ceramics Collection of the National Museum of Slovenia. It contains around 220 pieces of Chinese and Japanese porcelain, some of which were donated to the museum in the decades following its establishment in 1821. Their wealthy, former owners had likely followed the prevailing fashions of their time and acquired these objects through art dealers or received them as gifts. They tended to be made specifically for export, catering to the tastes of Western elites who cared little for the expertise on the origins of such objects.

Former owners were most likely attracted to the aesthetic and exotic qualities of East Asian fans, lacquerware, furniture, musical instruments or the samurai armours which are now part of the Collection of Objects from Asia and South America, housed in the Celje Regional Museum. Confiscated by the communist authorities immediately after World War II and marked only by their generic names in the confiscation records, their previous lives remain a mystery. What still speaks to us, however, is their exquisite beauty.

Souvenirs from distant lands

As Austria-Hungary began to build up its maritime identity in the late 19th century, the number of men from regions of nowadays Slovenia who joined the navy steadily increased. Many of them were attracted by the prospects of sailing around the world. For ordinary sailors and lower-ranking officers, this usually meant short shore leaves in the ports where the ships anchored. The higher ranks were often awarded opportunities to explore a little further inland.

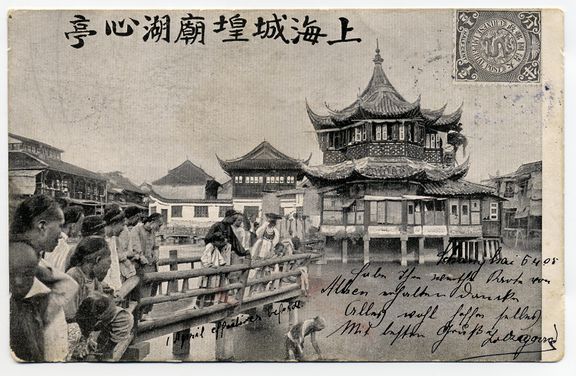

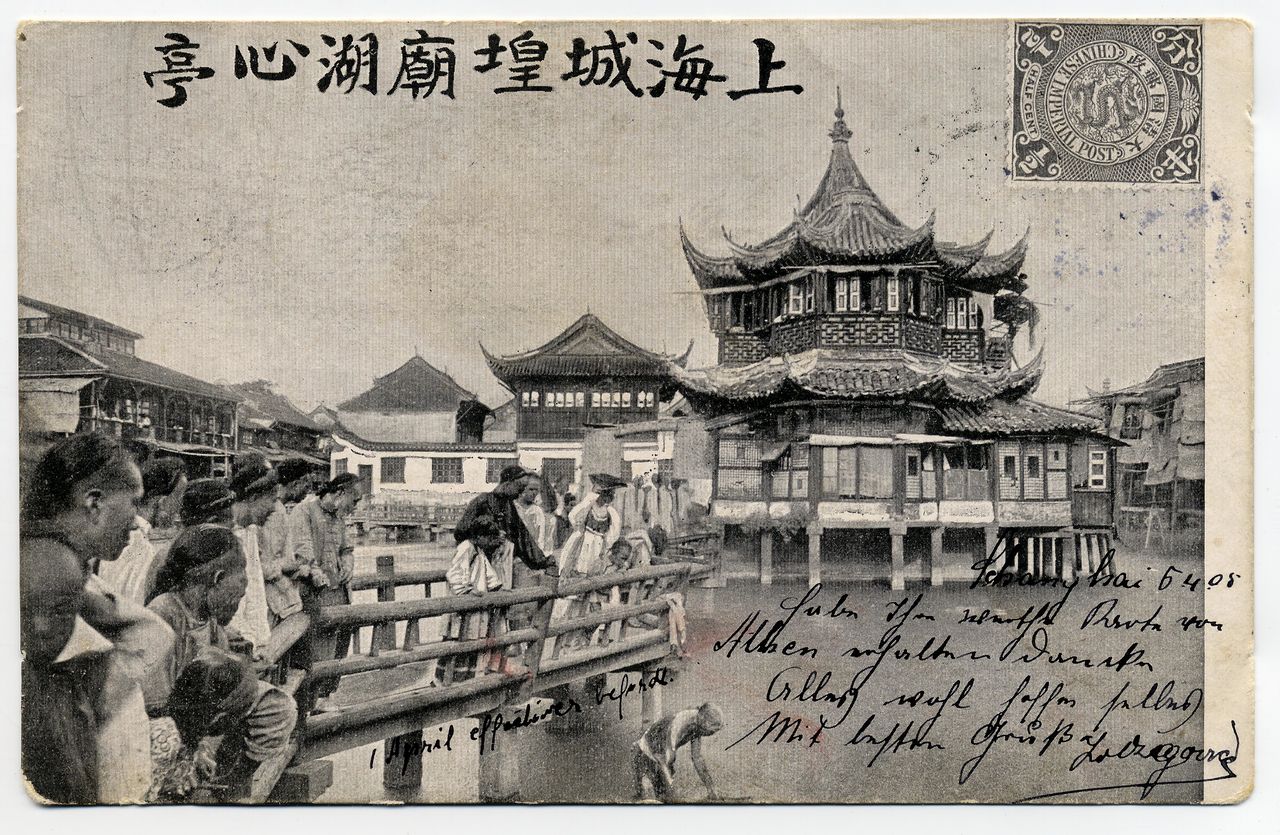

The growing presence of foreigners in certain port cities encouraged a local tourist industry. In addition to diaries, the belongings of navy personnel now kept in the Sergej Mašera Maritime Museum thus comprise various small objects. Fans, adorned knife handles and embroideries were all made specifically for foreign visitors. The turn to the 20th century is also dubbed the Golden Age of Picture Postcards, so it is not surprising that several of the navy men were avid postcard collectors. Some even brought back ready-made photo albums portraying famous sites, street scenes and portraits of locals. These were another common if more expensive souvenir of the time.

Postcards like this one from Shanghai's Yu Garden were a common way for navy personnel to share their travels with those back home. Ivan Koršič Postcard Collection, Sergej Mašera Maritime Museum, Piran.

Postcards like this one from Shanghai's Yu Garden were a common way for navy personnel to share their travels with those back home. Ivan Koršič Postcard Collection, Sergej Mašera Maritime Museum, Piran.

China in the living room

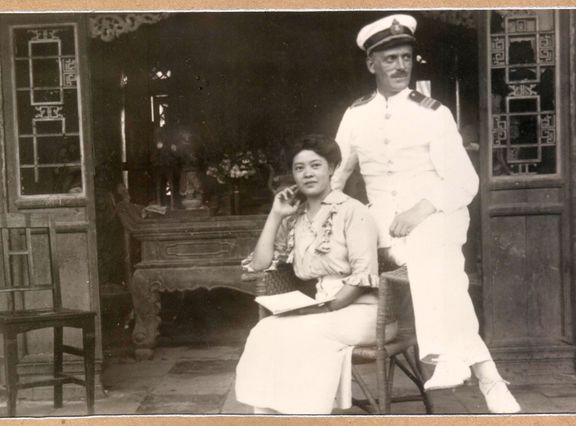

Among the naval officers, the story of Ivan Skušek (1877–1947) is the most fascinating. In 1913, he boarded the Austro-Hungarian cruiser S.M.S. Kaiserin Elisabeth, which was headed to Japan. When he stepped off the train at the Ljubljana railway station in the autumn of 1920, he was a great collector and promoter of Chinese culture. Namely, because of World War I, his ship had been redirected to Qingdao in China where they were to help German troops defend the port, besieged by the Japanese. Suffering defeat, the Austro-Hungarian soldiers were interned in war camps in Japan, while the officers were sent to Beijing. Among them was Skušek.

Ivan Skušek and his wife to be Tsuneko Kondō Kawase in Beijing, between 1918–1920. (The photo is kept in the library of the Slovene Ethnographic Museum, the original is kept by Skušek's great-nephew Janez Lombergar.)

Ivan Skušek and his wife to be Tsuneko Kondō Kawase in Beijing, between 1918–1920. (The photo is kept in the library of the Slovene Ethnographic Museum, the original is kept by Skušek's great-nephew Janez Lombergar.)

During his six years in the Chinese capital, he developed a specific aesthetic sensitivity for the Chinese heritage. He systematically collected various objects to set up a museum upon his return home. He envisaged the museum building to be a large-scale construction in the style of traditional Chinese architecture: to that end, he even brought back a model of a Chinese house. It seems he planned to display the objects set against authentic interiors of the homes of the Chinese elite. Sadly, his financial situation prevented him from making his ambitions come true.

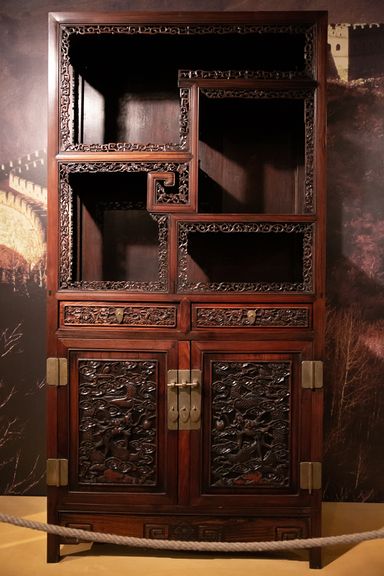

Stunning Chinese wooden furniture exhibited in the Skušek Collection at the Slovene Ethnographic Museum.

Stunning Chinese wooden furniture exhibited in the Skušek Collection at the Slovene Ethnographic Museum.

The Skušek Collection of about 500 Chinese objects, now housed at the Slovene Ethnographic Museum, is the largest collection of Chinese objects in Slovenia. It contains many high-quality items, some of them reportedly of imperial provenance: from richly embroidered textiles, paintings, albums, Buddhist statues, ceramics and porcelain to furniture, decorative wall screens and a model of a house. We also find items from coins, musical instruments, everyday objects to photographs, rare books and old postcards.

The most remarkable and valuable part of his collection is the various specimens of richly carved Chinese furniture. It is amazing to know that Skušek was one of the first Western collectors to discover the refined lines of Chinese wooden furniture in the early 20th century.

An exquisite Chinese wooden cabinet, one of the artifacts exhibited at the Slovene Ethnographic Museum in the Skušek Collection, the largest collection of Chinese objects in Slovenia.

An exquisite Chinese wooden cabinet, one of the artifacts exhibited at the Slovene Ethnographic Museum in the Skušek Collection, the largest collection of Chinese objects in Slovenia.

Skušek's home, where he lived with his Japanese wife, Marija Skušek (born Tsuneko Kondō Kawase, 1893–1963) and her two children from her first marriage, was frequented by the intellectual and artistic elite of Ljubljana. Crammed with various Chinese objects, this is likely where the city's leading architect Jože Plečnik (1872–1957) became familiar with the principles of Chinese aesthetics. Plečnik was a regular visitor to Skušek's flat and was much taken by its ceramic roof statues and garden furniture. Marija Skušek, whom Ivan had met in Beijing, also played a significant role in transmitting East Asian culture to the wider Slovenian public.

East Asia as a professional inspiration

Another collector of East Asian objects was Ivan (John) Jager (1865–1962). He was an architect and urban planner, who was sent to Beijing in 1901 to participate in reconstructing the Austro-Hungarian embassy[1] building damaged during the Boxer Rebellion the previous year.

The Austro-Hungarian Embassy in Beijing in the early-20th century. Photo album from the Skušek Collection, Slovene Ethnographic Museum.

The Austro-Hungarian Embassy in Beijing in the early-20th century. Photo album from the Skušek Collection, Slovene Ethnographic Museum.

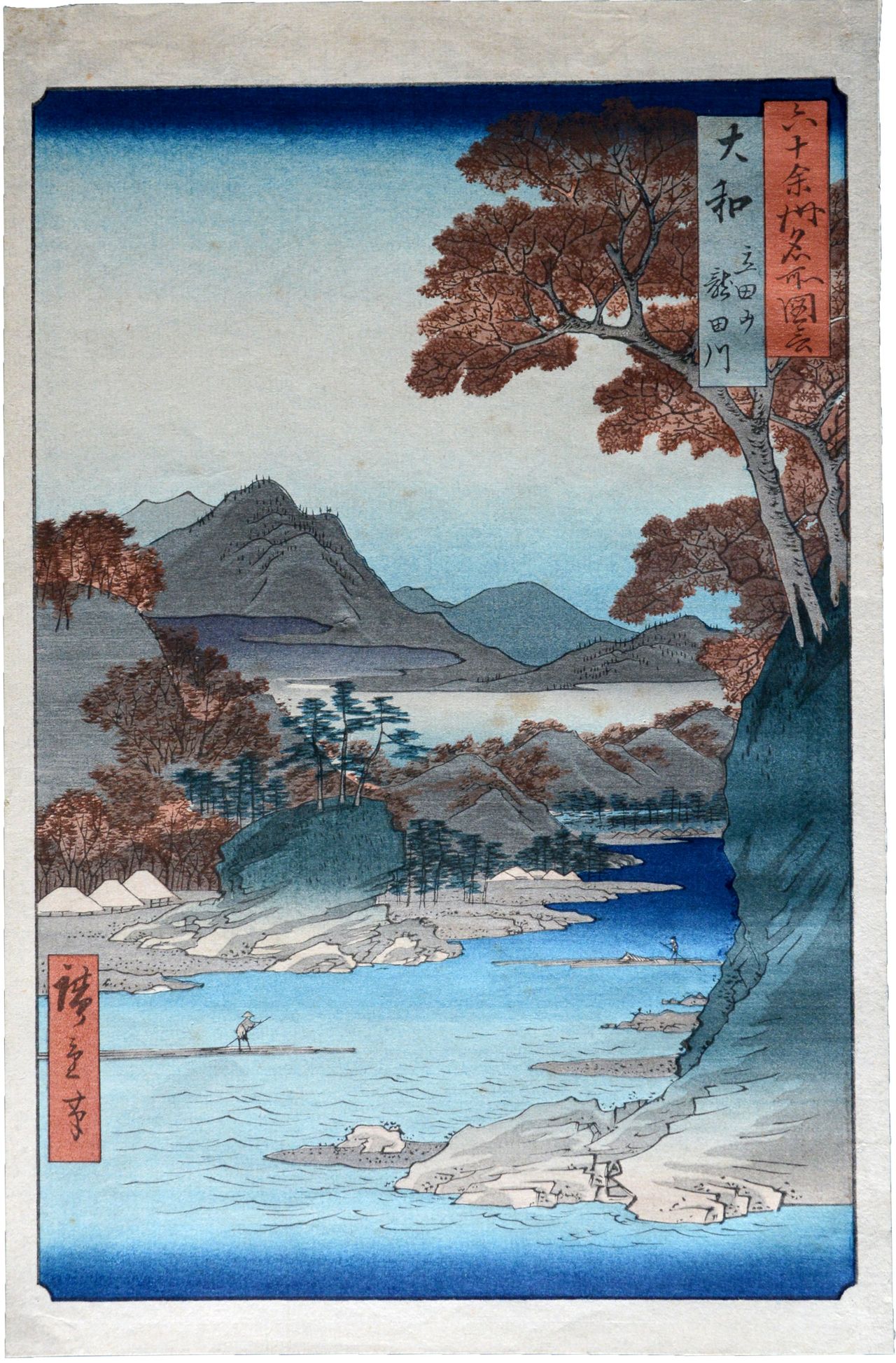

He stayed in Beijing for four months before travelling to Japan and further to the United States, where he became famous as the builder of Minneapolis. Although his stay in East Asia was rather brief, he assembled an admirable collection of Chinese and Japanese objects. Among the most impressive pieces are many Japanese sword handguards, Japanese Ukiyo-e prints and a variety of precious textiles. Of particular note is the four-piece Chinese screen decorated with floral and bird motifs. Originally decorating the imperial Summer Palace, it represents one of the finest examples from the emperor Qianlong period (1711–1799). His collection is now housed in Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SAZU) Library.

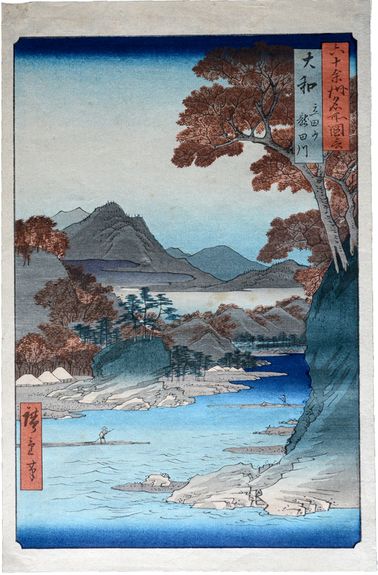

A 19th-century Ukiyo-e woodcut by Andō Hiroshige, Alma Karlin Collection, Celje Regional Museum, K 825.

A 19th-century Ukiyo-e woodcut by Andō Hiroshige, Alma Karlin Collection, Celje Regional Museum, K 825.

Bewitched by Asia

"I must go. Something inside me compels me to do so, and I will find no peace unless I follow this force." With these words, Alma Maximilliana Karlin (1889–1950) said goodbye to her mother in her hometown of Celje in November 1919, as she embarked on a journey around the world. Who was this extraordinary woman from the small Styrian town, who wrote in German, travelled the world on her own, working for money along the way, and sold 80,000 copies of her travelogue trilogy upon her return? What is her legacy and what objects did she collect on her travels?

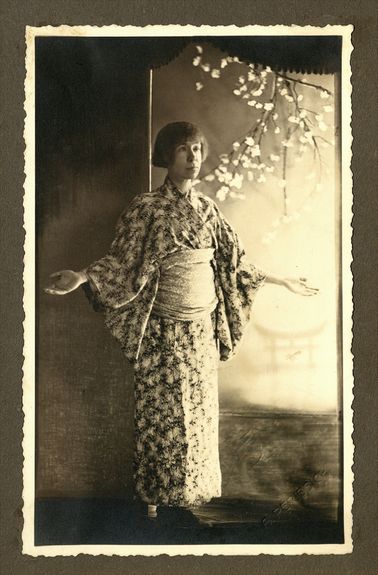

A portrait of Alma Karlin taken in the period 1920–1930. Part of the Manuscript Collection of the National and University Library, visible also on Kamra.si.

Alma Karlin portrait, 1920.

A portrait of Alma Karlin taken in the period 1920–1930. Part of the Manuscript Collection of the National and University Library, visible also on Kamra.si.

Alma Karlin portrait, 1920.

Karlin was a traveller, writer, journalist, collector and theosophist. She, too, wanted to use her collection to educate people. She ended up displaying it in her home. Her native house no longer stands, but you can visit her final residence on the outskirts of Celje. Many of the objects she amassed throughout the eight-year journey that took her to at least 45 different countries are now exhibited at the Celje Regional Museum.

Karlin's legacy is rich and varied. In addition to a large collection of objects, she also left published and unpublished works of fiction, journalistic writings, and extensive correspondence, all of which attest to her keen interest in foreign lands and cultures. These can be found in the National and University Library, Celje Central Library and Celje Museum of Recent History.

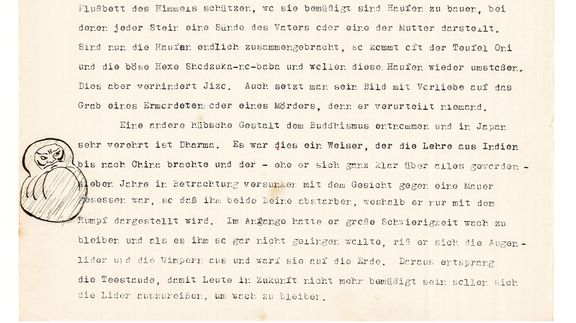

A sketch of the Japanese Dharuma figure in the margins of Alma Karlin's unpublished manuscript on religious beliefs and practices in the Far East. Alma Karlin Estate, Manuscript Collection, National and University Library, MS 1872.

A sketch of the Japanese Dharuma figure in the margins of Alma Karlin's unpublished manuscript on religious beliefs and practices in the Far East. Alma Karlin Estate, Manuscript Collection, National and University Library, MS 1872.

Karlin's tenuous financial situation determined her collecting strategies. During her journey, she had to work very hard to make a living and often found herself in financial difficulties. As a result, she was mostly able to purchase smaller everyday objects or souvenirs, in addition to those items she received as gifts. Interestingly, due to these limitations, her collection includes objects that were not of interest to the richer collectors of her time and are now, given their age, quite rare.

Smiling Buddha, Qing Dynasty, Skušek Collection, Slovene Ethnographic Museum.

Smiling Buddha, Qing Dynasty, Skušek Collection, Slovene Ethnographic Museum.

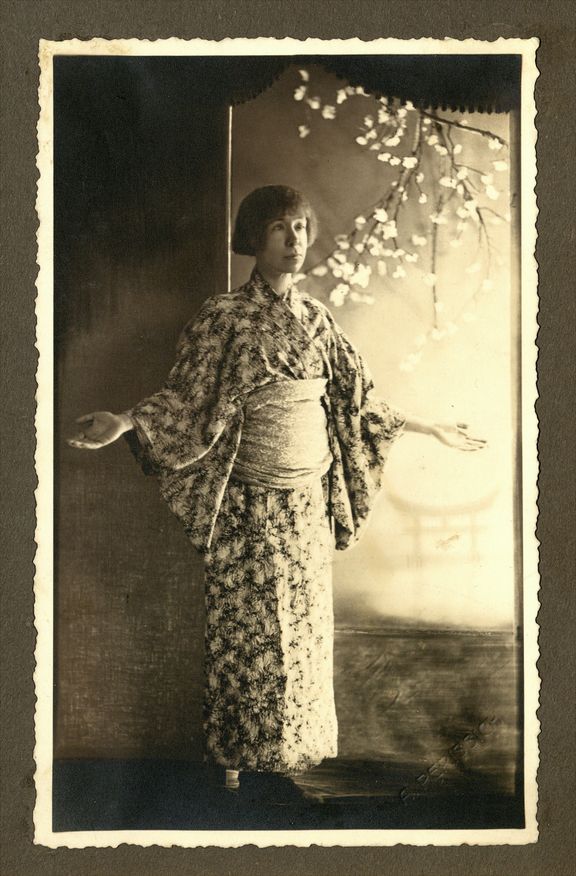

With its beautiful landscapes and fascinating culture, Japan made a particularly deep impression on Karlin. During her one-year stay in Japan (June 1922–July 1923), she worked at the German Embassy in Tokyo, which boosted her finances and provided her with the opportunity to step into contact with influential people. She was excited by her encounters with Japanese artists, who most likely inspired her to start learning how to paint in the traditional Japanese style. Her admiration for colour harmonies and universal beauty must have inspired her to purchase 17 Ukiyo-e prints, amongst which we find some famous Ukyio-e artists, such as Andō Hiroshige (1797–1858) and Utagawa Kunisada (1786–1865). In Japan, she also became very fond of the yukata, an informal type of kimono, and wore it even after returning to Slovenia. During World War II, she even took it with her to prison in Maribor, and when she later joined the Partisans.

Korean Fan, Alma Karlin Collection, Celje Regional Museum, K 80.

Korean Fan, Alma Karlin Collection, Celje Regional Museum, K 80.

Karlin also had a special passion for fans, which she collected from many different places. Unlike other East Asian fans in Western collections, Karlin's were not intended for the European market, but for domestic daily use. Few such fans have survived in collections worldwide, making Karlin's specimens especially valuable. Her other passions – probably both due to aesthetics and convenience, were miniatures and postcards.

Author bios

Nataša Vampelj Suhadolnik is associate professor at the University of Ljubljana. She is the leader of the national project East Asian Collections in Slovenia. Her research fields include East Asian material culture, collecting history, Chinese traditional and modern art, Chinese grave art and Chinese Buddhist art.

Maja Veselič is a sinologist and anthropologist, and a lecturer at the Department of Asian Studies, University of Ljubljana. Her research is on religion in East Asia, and the material and ideational exchanges between East Asia and Europe. She is a member of the project East Asian Collections in Slovenia.

Gallery

- ↑ For more about the embassy see https://vazcollections.si/predmeti/fotografija-ministrska-palaca-v-avstro-ogrski-legaciji-2/ (in Slovenian).