Difference between revisions of "GO2025 The City Yet to Become"

(video from NGUA - Balancing on the Border) |

|||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

| title = GO!2025: The City Yet to Become | | title = GO!2025: The City Yet to Become | ||

| subtitle = | | subtitle = | ||

| − | | blurb =While winning the bid for the European Capital of Culture speaks of a city's vision for the future, [[Miha Kosovel]] of [[Razpotja Journal|''Razpotja'']] magazine introduces the term transfrontal and reminds us of how understanding the history of a region can better prepare us for the mental and physical shifts needed in co-creating a new reality. | + | | blurb =While winning the bid for the [[Nova Gorica–Gorizia, European Capital of Culture 2025|European Capital of Culture]] speaks of a city's vision for the future, [[Miha Kosovel]] of [[Razpotja Journal|''Razpotja'']] magazine introduces the term transfrontal and reminds us of how understanding the history of a region can better prepare us for the mental and physical shifts needed in co-creating a new reality. |

}} | }} | ||

Revision as of 01:50, 19 December 2024

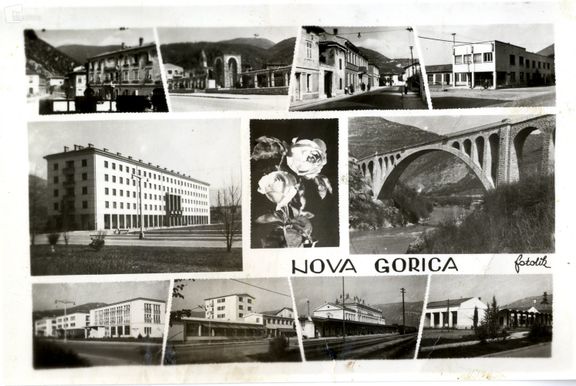

The Slovenian winner of the bid for the European Capital of Culture 2025 – together with the German city of Chemnitz (former Karl-Marx-Stadt) – is the youngest town in Slovenia, long-known as the Slovenian Las Vegas, since it is home to one of the biggest casino companies in Europe. Yet, the peripherisation process of the "westernmost lighthouse of our state that will warn us of the dangers of the reactionary West" was happening for many long decades. The nail on the coffin was the global financial crisis of 2008, which brought even the gambling-tourism industry to a stall. Nova Gorica had to find a new path and a new identity on its own. And culture was a nice way out for a newly-impoverished town with a peculiar, yet vivid, cultural scene.

A city made for peace

Nova Gorica was founded in 1947 after the Italian-Slovenian border cut the historically united territory of Goriška/Goriziano in half, putting most of the city of Gorizia/Gorica on the Italian side and most of its rural part in the Yugoslav (Slovenian) side. The end of World War II brought peace. Not only to the hostilities of more than 30 years since the intervention of the then Kingdom of Italy in the Great War against the Austrian-Hungarian Empire and the formation of the Isonzo Front on the beautiful Soča River connecting the region's Alpine part with the Adriatic Sea but also to the more than 20 years of fascism in the mid-war period when Italy occupied the entire region.

A postcard from 1910, featuring a panorama of Görz-Gorizia, today's Nova Gorica.

A postcard from 1910, featuring a panorama of Görz-Gorizia, today's Nova Gorica.

The presence of war is strongly felt in both cities: in the names of streets and squares, in the military graveyards and crypts, and in the many monuments, some of them with a strong artistic value of authors such as Boris Kalin or Negovan Nemec. But even though both sides contested the city of Gorica/Gorizia, peace was brought to the territory by making a new city, a new Gorica – Nova Gorica.

As Yossi Beilin – one of the architects of the Israel-Palestinian peace agreement that got the Nobel Prize but was never materialised – told Slovenian reporter Ervin Hladnik Milharčič (Razpotja, no. 29), they studied similar border issues in Europe and found a good example in our city/ies:

Nova Gorica was a city created so that there would no longer be a war between the two parts: a city that would stop the wars.

There are not many cities that commemorate the war as much as here. Not just the museums or micro-museums owned by private collectors, but also the cultural and communal projects. One of the largest is surely the Walk of Peace which transfrontally connects the towns, museums and sites of the Isonzo Front with a hiking route and is one of the engines of the reanimation of the heritage of the trenches and caverns along its path.

A city of smugglers

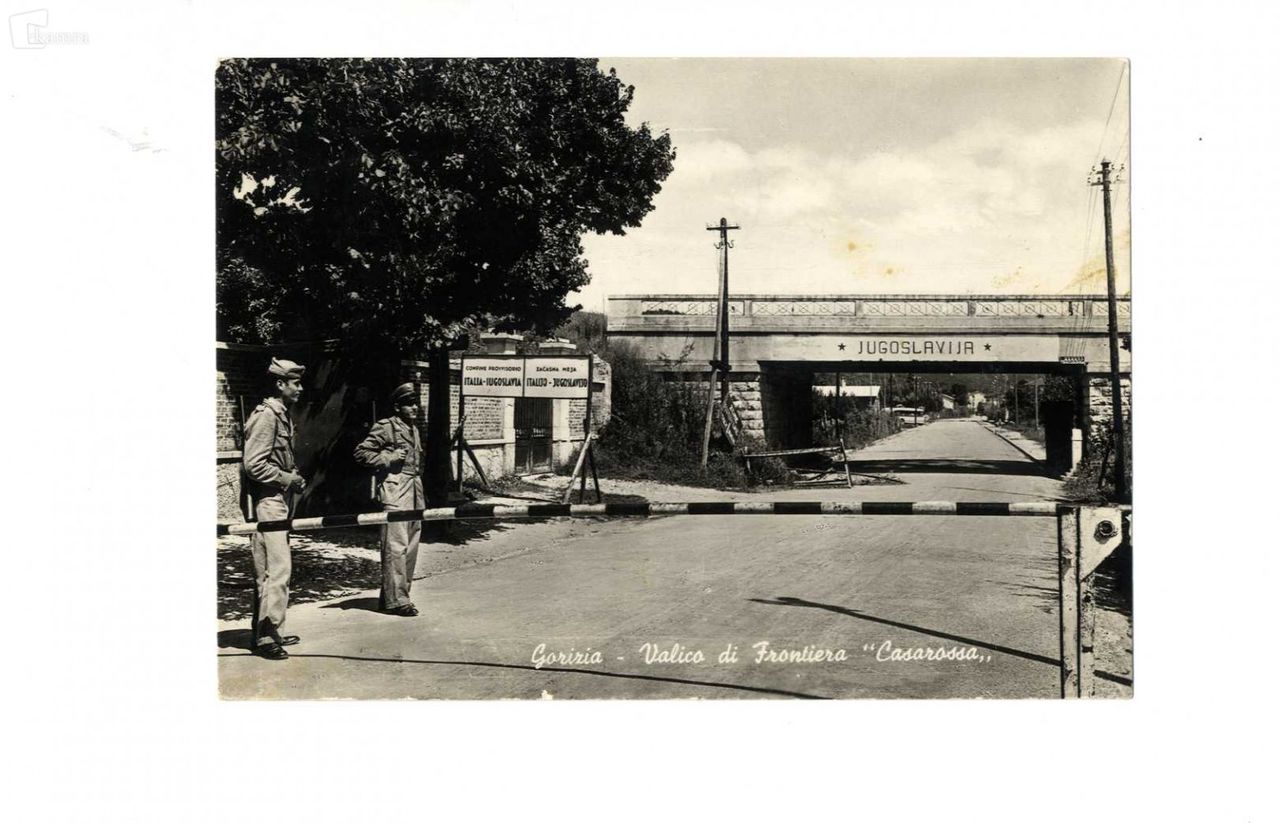

On the eve of Slovenia's inclusion into the Schengen Area in 2007, one of the leading artists of the region, Anja Medved, a film director specialised in memory documentation, did a project in the former border control check-point in the middle of both cities. The project was called Smugglers' Confessionary.

The idea was that after all those years of hiding and smuggling goods from one city to another, people would come to this place of division and police control and would confess their sins: stories about smuggling jeans, schnapps, meat, but also stories about avoiding political (Yugoslavia) or moral (Italy) censorship in cinemas, music and books. This (and similar projects in her decades-long opus) was very well accepted as it addressed the peculiarity of everyday life in the transfrontal region.

The focus on the border shifted from the zealous national identity imposed by the national states on the border towns (the so-called bastions of the nation) to a specifically local – but at the same time universal – identity of duality. In this identity, the parallel memories and interpretations meet and coexist in a complex ball of wool of counternarratives that wait for every individual to discover and weave a mosaic tapestry out of it.

A 1950s postcard of a border crossing in Rožna Dolina, Nova Gorica

A 1950s postcard of a border crossing in Rožna Dolina, Nova Gorica

If we could name one obsession in the territory, we could surely say it is the concept of the border as a unique space of non-singularity. In this place, everything simultaneously has its counter-meaning.

A few of the more visible consequences that have organically grown out of Medved's project are surely Carinarnica (an experimental, NGO-led cultural hub) and the Museum of Smuggling (a micro-museum led by the regional Goriška Museum). Both are situated in the former border-crossing blocks between the cities Nova Gorica and Gorizia.

Carinarnica, the welcome product of recycling a former border-crossing customs building into a culture centre, in Nova Gorica.

Carinarnica, the welcome product of recycling a former border-crossing customs building into a culture centre, in Nova Gorica.

The smuggling in the conurban area was never just the smuggling of goods but always also the smuggling of content and identities. (Identity Smugglers was the name of the 2016 documentary film directed by Marija Zidar in which the aforementioned Ervin Hladnik Milharčič, himself from Nova Gorica, took a journey of discovery of the Slovenian western border.).

This "identity smuggling" can easily be seen in the topics of the film sector – surely the region's strongest and most transfrontally-connected cultural field – in the mentioned opus of Anja Medved's institute KINOkašča/CINEMattic, in the projects of the transfrontal Kinoatelje, in the films of Italian director Matteo Oleotto (Zoran, My Nephew the Idiot) or the award-winning Slovenian director Gregor Božič (Stories from the Chestnut Woods), which have at the centre the misunderstanding and the mixed identities in the border area and many times mix the documental with fantasy.

But we can also see this in the theatre field. Theatre is very strong in both cities, since there is a national theatre in Nova Gorica and a communal theatre in Gorizia. These tendencies are especially in the opus of Neda Rusjan Bric and her biographical dramas of significant figures from the territory, such as actress Nora Gregor or architect Maks Fabiani, all with mixed identities that were tragically crushed by the nationalistic 20th century (Neda Rusjan Bric is also the artistic director of Nova Gorica's ECoC). We can also find related approaches in the newly formed experimental documentary theatrical group Teater na konfini led by actors Maja and Miha Nemec.

Milko Lazar and Zlatko Kavčič, both internationally renowned musicians as well as recipients of the Prešeren Award, performing at the Nova Gorica Arts Centre (the concert was later release on a CD called Ena/One), 2013

Milko Lazar and Zlatko Kavčič, both internationally renowned musicians as well as recipients of the Prešeren Award, performing at the Nova Gorica Arts Centre (the concert was later release on a CD called Ena/One), 2013

Surely the most-often smuggled cultural good is music, especially jazz music. Or maybe, the smugglers here are the smuggled – the musicians. A few decades ago, the notorious drummer and percussionist Zlatko Kaučič formed a strong and fruitful school of jazz and with it a thriving jazz scene made of many bands, even more individual projects of young musicians from both cities and beyond.

The scene, which is also very strong compared to the national level, struggles with the disappearance of venues but tries forming new content in some unusual places, like the former mortuary of the abandoned Jewish cemetery. Besides jazz musicians, jazz festivals like to cross borders and are surely one of the most visible transfrontal connections. Brda Contemporary, Music of the World, October Jazz, Jazz and Wine are some of the festivals organised by people and organisations from both sides of the border or taking place in both cities.

A new city

On the edge of the two cities, lies the monumental train station – built in 1906, it's one of the few buildings that went to Yugoslavia after the war, yet it exists in the identity of inhabitants from both cities. Here, there is a common square, inaugurated on 1 May 2004, when all of the European heads of state came here to celebrate the entry of 15 new states into the European Union, Slovenia among them. The common square still doesn't have a common name. On the Italian side, it is called Piazza Transalpina, a name that resonates with the golden years of Gorizia, when the Transalpina-Bohinj railway was constructed and connected these territories with its capital Vienna; on the Slovenian side, it is called Trg Evrope (Square of Europe), a utopic vision of a future Europe in which – like our anthem says:

That all men free / No more shall foes, but neighbours be.

The building of today's Nova Gorica railway station, a postcard from the early 1920s. (Photo from the regional library portal Kamra.si.)

The building of today's Nova Gorica railway station, a postcard from the early 1920s. (Photo from the regional library portal Kamra.si.)

What seems like a failed attempt of unification, an impossible mission of the political class of both cities to agree at least to a common name for a common square, could be interpreted in a dialectical tone; and that's what I think the bid for ECoC is about. The main goal is not the uniformisation of the two cities, or even worse, the invention of a common, nonproblematic identity, a minimum standard upon which inhabitants of both cities could agree.

Instead, the main goal is unification through a meeting of the duality in which neither loses its uniqueness but co-creates a new reality. By working together, Nova Gorica and Gorizia form a new city, that transcends the two cities, transcends the nations, transcends the administrative borders. The new city is the mere praxis, a schoolyard for a postnational approach to everyday life.

The coming together of the city is at once a goal and a symbol. There are many dualities in today's world that need to be addressed. There is the duality between rural and urban that's addressed in the engagement of the artist collective BridA in developing contemporary art projects in the rural area, or the seed bank of old varieties of local fruits and vegetables developed by the France Bevk Public Library, Nova Gorica.

There is the duality of languages and the goal of passive polyglotism. Every year, the gap is widening between the periphery and the state capitals, the ongoing brain drain, the centralisation not just of public funds and assets but also of ideas and minds.

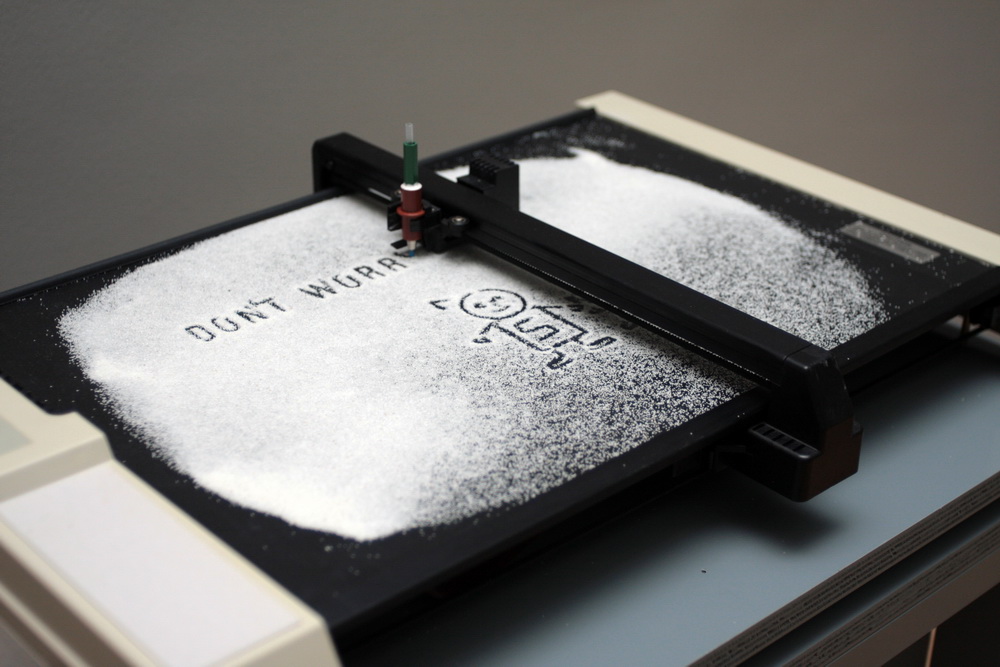

Nanoplotter uses a plotter, an obsolete printing machine from the 1980s, adapted to an uncommon operation. By the artist collective BridA at the U3, Museum of Modern Art, Ljubljana, 2010.

Nanoplotter uses a plotter, an obsolete printing machine from the 1980s, adapted to an uncommon operation. By the artist collective BridA at the U3, Museum of Modern Art, Ljubljana, 2010.

These issues are addressed in the editorial sphere by the magazine Razpotja (Crossroads) – one of the leading cultural periodicals in Slovenia trying to decentralise the public discourse on culture, humanities, and politics – and in Goriška Humanist Association's bookfair and literature festival City of Books.

Decentralisation in the art sphere is surely well addressed by the young, but propulsive School of Arts of the University of Nova Gorica, which through new artistic approaches and media is trying to reflect the transfrontal reality. Surely, the duality between industry and culture is very well addressed by last year's curator of Pixxelpoint (the oldest Slovenian festival for digital art) Peter Purg in reprogramming the slot machines of the town's main casino to make an art installation. And many more.

The importance of Nova Gorica-Gorizia ECoC is surely manifold. It's an attempt to reopen the conception of a national cultural centre. It's a shot at what it means to make a transfrontal European city. For sure, it's a sandbox for learning how to overcome the atrocities of wars, maybe as an example for other cities and regions divided by hostilities.

Author bio

Miha Kosovel is editor of the magazines Razpotja and November, programme editor of the City of Books Festival and the cultural hub Carinarnica and an activist engaged in the topics of decentralisation and NGO culture.